Oprah Winfrey and Bruce Perry address the issue of healing from trauma in their book, What Happened to You? In a chapter on Coping and Healing, they explore the impact of relational deficit in the early years of a child’s life; what neglect and parental conflict does to a child’s development, their worldview and their stress response; and the importance of an understanding, nurturing and patient carer/parent/therapist for healing to occur. In the process, they discuss, in depth, the nature of neglect, differences in the way individuals are impacted by trauma, behavioural manifestations of adverse childhood experiences, and the road to healing, including creating a new worldview.

This chapter of their book is very rich with stories, insights, principles and personal disclosure by Oprah – disclosures that are enriched by observations by Bruce on her life experiences. Oprah, herself, and the vast work that she does in the area of trauma healing, is an exemplar for coping with, and healing from, trauma. What she has learned through her own life experience and ongoing discussions with Bruce over many years, has led to her establishing the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy for Girls (OWLAG) in South Africa.

The emotional environment in early childhood

Bruce maintains that the quality of the emotional climate in early childhood impacts our worldview and our stress response. If there is stability, nurturing and predictability, our brains and our behaviour can develop. If the opposite exists, this has an adverse impact on our childhood development and our capacity as an adult to deal with challenges and stress. We can develop the mindset that we are not lovable or not worthy of people’s attention. Dr. Gabor Maté utilises a process he calls “compassionate inquiry” to unearth these negative self-stories – vestiges of an early life lived in an environment of neglect.

Bruce highlights the fact that different, deficit emotional environments can result in very different traumatic effects. He illustrates this point by an in-depth comparison of two boys who manifested their traumatic upbring in contrasting ways. His explanation shows clearly why one boy became fearful and aggressive while the other “had no feeling at all” and engaged in threats and thefts. His description of their respective adverse childhood experiences and their differentiated impacts brings into sharp focus the key role that quality relationships play in early childhood.

This discussion of the differences in personal development of the two boys led Bruce to assert that an important consideration is not only “what happened to you?” but also “what didn’t happen for you?” – in terms of the behaviour of a parent/carer who provides undivided attention (in lieu of distracted attention), gentle touch (rather than physical abuse), consistent nurturing (instead of an on/off approach) and regular reassurance (instead of a belittling attitude). Not only does the quality of relationships in early childhood impact brain development but also the development of social and motor skills. Bruce contends that “relationships are the key to healing from trauma” because trauma often results from deficient relationships.

An environment of conflict

Bruce notes that if you are a young child and you are in an environment of parental conflict, you have limited options. You are too young to flee and unable to fight as you are easily overpowered and may draw physical attacks from either or both parents. Often in this situation, a child will dissociate – retreat to their inner world. Dissociation becomes a problem when it is prolonged or becomes a habituated response to everyday challenges – this can lead to what is termed a dissociative disorder. I can relate to dissociation as a stress response as my parents had frequent verbal and physical conflicts over my father’s alcoholism and gambling – my mother would berate him over his misuse of our family income. This would sometimes escalate into a physical attack on my mother, on a number of occasions this put her in hospital.

When I was young, my natural response would be to dissociate from the traumatic experience, as flight or fight was not an option – fight was out of the questions as my father was a very successful professional boxer. However, as I reached the age of 12, I used to get on my pushbike and ride into the night as fast as I could (flight response), hoping that when I returned the conflict would be over. The physical exertion of bike riding at speed served to release some of my pent-up tension and fear from the conflict.

Both Bruce and Oprah make the point that there is a positive side to dissociation in that it could be a life-saving response in some situations but is also part and parcel of what each of us do every day – e.g., day dream. Bruce contends that the “capacity to control dissociation behaviour is very powerful” – it underpins our capacity for reflection and focus and to achieve a “flow state”. I experienced a number of personal traumas in my early childhood and adulthood, including a serious care accident in the family car when our car was hit on the side by another car, rolled a number of times, went over a 10 foot embankment, and came to rest on its hood. I have learned to control my dissociative behaviour and, as a result, developed high levels of reflective cognition and focused behaviour – reflected in my PhD, Professorship and this blog (this is my 700th published blog post for my Grow Mindfulness blog).

Reflection

“What Happened to You” by Bruce and Oprah stimulated a lot of reflection for me and in some instances, “flashbacks” as well. I began to appreciate more how my five years spent as a contemplative monk (from ages 18 to 22) served to provide me with a highly structured, stable, reflective and meditative environment with high quality relationships that together enabled me to self-regulate after a traumatic upbringing in a conflicted parental environment. In my upbringing, my mother’s unconditional love and support offset to some degree my father’s (PTSD-induced) behaviour.

I am sure my period of development in an environment of daily silence, meditation, prayer and study helped me to achieve a degree of peace and tranquility (sometimes punctuated by moments of panic over my deteriorating home situation). As I grew in mindfulness, I was able to develop resilience, a positive mindset and the ability to find refuge in meditation.

________________________________

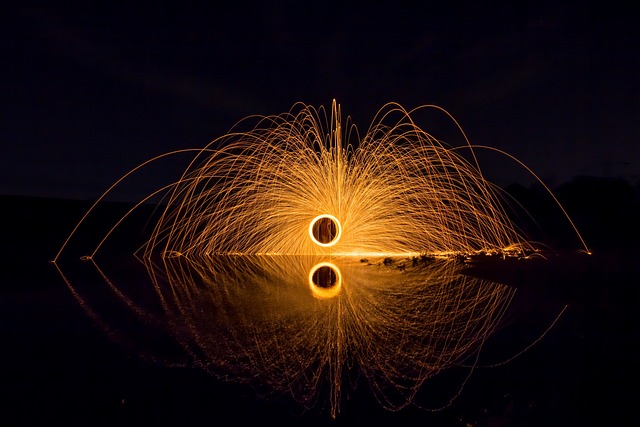

Image by Luisella Planeta LOVE PEACE ?? from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group, and the resources to support the blog.