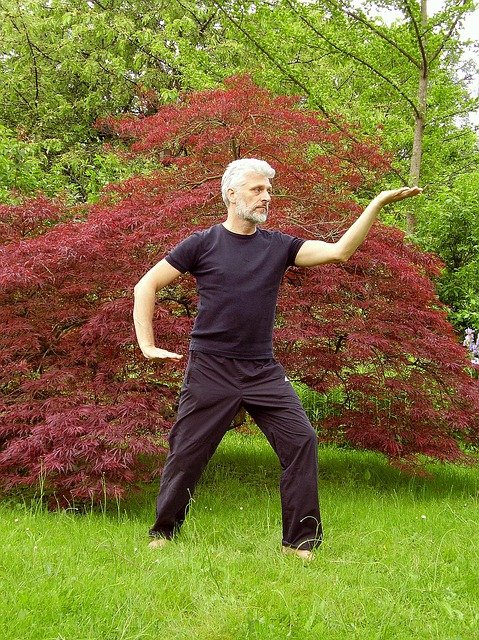

While my focus here is on Tai Chi practice, some of the principles I will discuss have relevance to other forms of mindfulness practice. For some time now, I have been practising Tai Chi on and off, with a few periods of sustained daily practice over several months. In my current sustained effort at daily practice, I have changed a number of strategies to help me maintain the momentum of practice – and often it is about developing a momentum like I have been able to achieve with my blog (over 500 posts).

I am acutely aware of the research that establishes the benefits of Tai Chi for my physical and mental health and overall sporting fitness. I devoured Dr. Peter Wayne’s research into the active ingredients of Tai Chi. So, intellectually, I know about the many benefits of Tai Chi. However, sustained daily practice requires a commitment – an exercise of both mind and heart, incorporating an emotional attachment to the end goal(s).

Strategies you could adopt to sustain a daily practice

Commitment to a daily practice also involves flexibility, adaptability and adjusting your thinking. The strategies identified in the following list are based on what is working for me at the moment:

- Flexible timing – most of what you read about habit forming advises you to adopt a set time each day for your practice. However, some days it is not possible to achieve a set time owing to other commitments of work or family (or writing a blog). The tendency then is to drop the practice for the day, rather than adopt a more flexible approach and work out a time when you can fit in the practice despite other commitments taking up your allocated time slot. Being flexible about timing and location enables you to sustain your daily practice.

- Prioritising – as you build up awareness of how important your daily practice is to your overall life, you can tell yourself to give your practice a priority in your daily schedule – in other words, no matter what else you have to do, somehow you have to fit in your daily practice. It becomes a “must do” rather than a “nice-to-do”.

- Establishing a personal mnemonic – capture the benefits of your practice in the form of a mnemonic so that you can quickly recall the benefits as an added motivator. This requires you to research the benefits of your daily practice and to keep them uppermost in your mind.

- Mentally linking the benefits to a recent or forthcoming event – relevancy aids motivation, so if you can think about something that has happened or is about to happen and focus on what benefits your practice would bring, you are adding to your motivation. For example, if you have recently heard about the impact of Alzheimer’s disease on a relative, you are reminded of the benefit of Tai Chi for improving your mind and body and developing your mind-body connection. If you are about to play a game of tennis, you could think about the benefits that Tai Chi would bring to your tennis playing, e.g., timing, coordination, balance, flexibility, and concentration.

- Being adaptable as circumstances change – the need to work from home as a result of enforced isolation brought on by the pandemic, has necessitated a lot of adjustments, especially when both partners work from home. As part of your negotiations about how things will operate in this home/work environment, you can negotiate time(s) and location for your daily practice. Instead of putting off your practice, you could choose to close the door of your practice room for the required period so as not to disturb, or be disturbed by, your partner. Negotiating arrangements with your partner is an essential aspect of maintaining positive mental health when forced to work from home.

Reflection

Over time circumstances change, so to maintain a daily practice requires flexibility, adaptability, and strategies to keep the benefits of your practice at the forefront of your mind (so that you will have the motivation to overcome obstacles as they arise). As you grow in mindfulness through Tai Chi, meditation, yoga or other mindfulness practices, you can become more self-aware about what causes you to procrastinate or put off your practice. You can also strengthen your motivation through the reinforcement that comes with practice and the development of unconscious competence in your practice activity.

________________________________________

Image by MichaelRaab from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.