Since I started participating in the Creative Meetups organised by the Health Story Collaborative I have been writing poems. It’s as if there are feelings inside me that need to get out. It reminds me of my PhD supervisor who told me at one stage of my extended procrastination, “You have a doctorate inside you, unless you let it out, it will undermine whatever you are doing.” Once I wrote the PhD, it released a whole new world of opportunity.

Over time, our disposition to forgive and our capacity to offer forgiveness to others and ourself will develop almost invisibly if we grow in mindfulness through appropriate practices, such as forgiveness meditations. The following poem grew out of my mindfulness practices and Meetup reflections:

Paternal Forgiveness

I didn’t forgive you while you were alive.

I didn’t even forgive myself.

Now I don’t know how to say sorry to someone who has passed.

You served in the army during World War 2 before I was born.

You spent four years in Changi and worked on the Burma Railway.

Shortly after your army discharge, you reenlisted.

When I was four, you left to work in Sydney and Woomera.

And served 18 months with the Occupation Forces in Japan.

There you were an “enemy stranger” in a foreign land.

In your absence, Mum was seriously ill following the birth of Michael.

You returned for two weeks to take Mum and my two brothers to Brisbane.

While baby Michael spent time with your sister before getting ill himself.

My younger sister and I were separated and left with different relatives in Melbourne.

Three month old Michael was eventually placed in a Founding Home.

When Mum returned a month later to collect the three of us, you told her that Michael had died while she was in transit.

I spent 18 months in an orphanage at the age of four while you were away.

Those were the months of my imprisonment and harsh treatment, shared by my younger sister.

Though we were separated from each other by the Institution.

Mum was only allowed by the Institution to visit us monthly.

It was only then that I saw my brothers and my sister, despite her being in the same Orphanage.

I felt isolated and alone.

When you returned from Japan, you became an aggressive alcoholic.

As a young child, I would freeze and dissociate when your rage flared.

As I got older, I would take flight by riding my push bike into the night as fast as I could.

I didn’t understand PTSD – no one did at that time.

I had not been where you had been or seen what you saw.

I didn’t see the triggered images that tormented you.

The war, the explosion, hospitalisation, capture and prison life.

You suffered the loss of mates killed in action or dying from cruelty or malnutrition while you were in Changi or working on the Burma railway.

You experienced unimaginable horrors.

I understand now that alcohol was your way to drown your pain and sorrows.

To block out the horrific images.

I forgive you and forgive myself for my harsh judgments – I didn’t understand.

It was easy to take sides when you were drunk and wasting our income.

While Mum slaved away at the local Woolies to keep us afloat.

And vented her anger and frustration at night.

As an adult, I had to take Mum away from your violence for her survival.

I was fearful at the time that you would try to find us.

As we took shelter in the small rooms at the back of a General Store.

The separation proved to be a godsend.

You both improved your lives.

With new partners eventually and a healthier way of life.

You even gave up alcohol and walked an hour every day.

On Sundays you took Mum to Church.

But we were not able to reconnect.

You had been a professional boxer, winning 20 of 22 fights.

You won trophies for tennis and athletics.

You became Player Coach of a Reserve Grade AFL team in Brisbane.

I am truly grateful that I inherited your genes.

The fighting spirit, resilience, determination and fast reflexes.

All of which have helped me in my tennis and my work and life.

I am sorry that I did not know what you were going through.

That I saw myself, instead of you, as the victim.

That I did not acknowledge your unbearable pain and unbelievable courage and tenacity.

____________________________________________

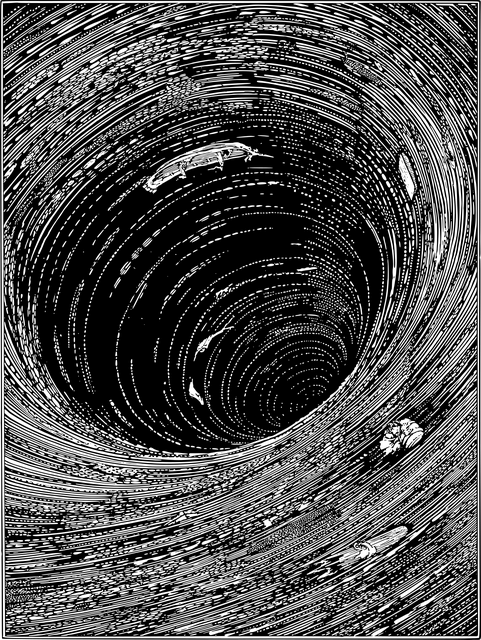

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site and the resources to support the blog.