Ryder Carroll in a TEDx Yale Talk titled, How to declutter your mind – keep a journal, highlighted the role a journal can play in helping you to overcome the busyness in your life and lead what he calls an “intentional life” – a life lived with intent, focus and purpose. He maintained that we cause ourselves stress and anxiety by cluttering our minds with things that are not important and as a result lose sight of things that matter to us.

Our thoughts are discursive – one thought follows another in an endless stream. These thoughts and our busyness are often driven by expectations – our own and those of others in our life. As discussed previously, expectations can hold us captive and erode our freedom of choice. In some organisations, busyness has become a sign of importance – where the expectation is to be “seen-to-be-doing”, rather than being and achieving.

Ryder states in his presentation that today we suffer from “decision fatigue” resulting from “choice fatigue”. At every moment of the day we are confronted with choices and decisions – you only have to try to buy a simple product at a supermarket to experience this at a micro level. Decisions take time and energy and time is a non-renewable resource – the very words, “take time”, indicate that we consume time in our lives as we live out our choice-making and act on our decisions.

Create a journal to declutter your mind

Journalling has been shown to be beneficial for many reasons – not the least of these being to improve our overall well-being. Ryder, however, emphasises the necessity of a journal to help declutter our minds and free our thinking to focus on the things that are important to us. He suggests that a journal can serve the purpose of a “mental inventory”, where you record your tasks, events and notes as a way to better manage the present, track what has happened in the past and plan your future.

He provides a simple approach to journalling that he calls a “bullet journal” and provides a very brief video to explain this approach. The name derives from the methodology of creating different forms of bullet points to identify tasks, events and notes.

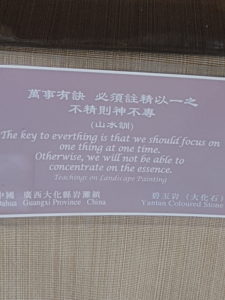

Ryder highlights the importance of reflection to underpin his approach to mind management. He suggests that it is not enough just to record the relevant information but also to review what has been written. He offers three considerations that can form the basis of a daily, weekly or monthly review of your individual journal entries:

- does it really matter?

- is it important to achieve or realise?

- is it merely a distraction?

Recording without reflection is just reinforcing busy behaviour – without review there is little development of self-awareness and self-management. The review can be strengthened by consciously developing a focus for our time and energies.

Developing focus and productivity through small projects

Ryder’s approach to developing focus is to identify things that are important to us to achieve and to frame them as small projects (breaking down larger projects into smaller parts or milestones). He then suggests that these are incorporated in the monthly plan of your bullet journal, while the relevant tasks that make up an individual project can be collected in a project plan or what he describes as a “collection”.

The small projects act as a point of focus in any given month, serve as a way to channel time and energy, engage your curiosity and build a sense of self-efficacy through achieving identified milestones and project outcomes. Breaking goals down into achievable parts is a proven approach to increasing your productivity. Ryder suggests that the small projects should be something that is within your control – they are free from externally imposed barriers, they are expressed as achievable tasks/outcomes and can be done in the limited timeframe of a month (which lines up with the monthly planning cycle that he recommends). These small projects give us a sense of control and increased agency which serve as a foil to the sense of losing control which comes with endless busyness.

As we develop our journal to declutter our mind and manage our time and energy, we can free ourselves to grow in mindfulness through reflection and meditation and open our lives to less stress and more creative opportunities.

____________________________________________

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Image source: courtesy of raydigitaldesigns on Pixabay

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.