Kylie Orr in her novel, The Eleventh Floor, has her lead character, Gracie, comment after experiencing the impact of deceit in a relationship, “I was committed to loving up close, to being open, vulnerable”. While Gracie acknowledged that “there is danger in that”, she was willing to take the risk inherent in vulnerability because “a life held together by lies fell apart so easily”. Being vulnerable exposes us to the possibility of being harmed by someone else emotionally, intellectually or physically – it involves showing our true self with our emotional weaknesses, character faults and physical defects.

Vulnerability, however, is a source of strength. It underpins perseverance and resilience, facilitates sustainable relationships, enriches our contribution to community, and enables the writing of an entertaining and enlightening memoir. To access the strength in vulnerability we have to face up to being vulnerable – we need to name our feelings (e.g., fear of rejection) so that we can tame them.

Perseverance and resilience

Contrary to the Alpha Male depiction of power, dominance and the trappings of success, Lance Alfred (legally deaf NBA player) contends that perseverance and resilience in the face of adversity require a totally different orientation. He maintains that there is real strength in vulnerability – owning up to our feelings, being authentic, having self-awareness and self-intimacy (acknowledging our own thoughts, actions and consequences), forgiving others, moving beyond other people’s expectations to be our true self, accepting our inadequacies and mistakes and overcoming the fear of failure.

When we fear failure we can be trapped by inertia – unable to move forward beyond the current challenge. In her novel The Brightest Star, Gail Tsukiyama describes a time when Chinese-American actress, Anna May Wong, was making her stage debut In The Circle of Chalk and was terrified that her speaking voice and singing were not up to the expected standard (after spending so much time acting in silent movies). The critics were having a field day about her voice but she acknowledged this weakness and “went on the offensive”, hiring a voice coach. Despite the criticisms of the critics, the show had a “successful run”.

Sustainable intimate relationships

We can hide our fear of being vulnerable in a relationship in multiple ways including excessive criticism of the other person, aggression (anger), withdrawal (silent treatment), overcontrolling or projecting our own weaknesses or fears onto the other person. These defence mechanisms only serve to push the other person away, to wound them and disable them. While they provide protection for our ego and self-concept, they create a barrier to a sustainable intimate relationship.

Tara Brach provides a meditation which enables us to explore the ways that we create separation or distance in a relationship by resorting to defence mechanisms to ward off vulnerability. In the meditation, we are asked how we are impacting our relationships(s) by avoiding vulnerability. The challenging questions relate to self-protection, projection, judging, withholding, distrusting or engaging in “superior conceit”. Tara points out the power of being vulnerable (overcoming our natural defence mechanisms) in terms of building closeness and sustainable relationships.

Enriching our contribution to community

Tara tells a number of stories where being vulnerable led to someone else finding strength to manage a disturbing or embarrassing circumstance. One of the features of the Creative Meetups hosted by The Health Story Collaborative is the vulnerability shared by participants in the monthly, online meetings. Participants are people experiencing chronic illness or disability or are in a caring role. They willingly share their pain, difficulties in coping, inability to think clearly, physical weaknesses, anxiety or depression or lack of energy.

The level of openness and trust enables individuals to express their vulnerability without fear of being taken advantage of, or being consciously harmed by anyone else present. Vulnerability, enhanced by the culture of sharing and collaboration, builds closeness and healing. There is the implicit recognition that being vulnerable is integral to the human condition.

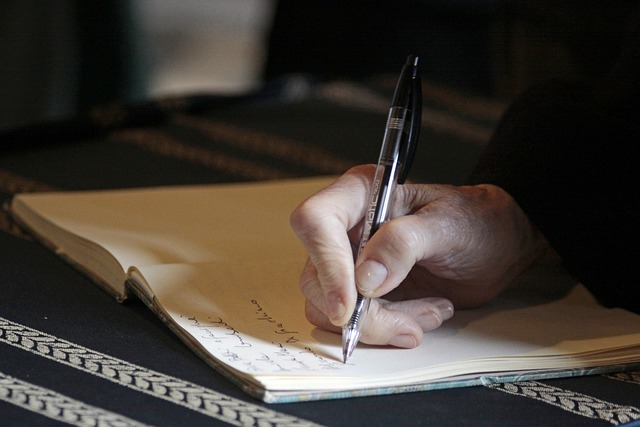

Developing a memorable memoir

In the Art of Memoir, Mary Karr, stresses the need for authenticity – revealing our real self, not the projected self or the deemed “virtuous self”. She highlights the importance of being vulnerable rather than self-protective. She sees the memoir as a personal unfolding that is sometimes painful – an honest exploration of our “inner landscape”, not just a recording of external events. Mary suggests that as we are developing our draft memoir with recalled stories “what burbles up onto the page is what is exclusively yours, both as a writer and a human being”. She maintains that we have to trust the power of truth enough to “keep unveiling yourself”, despite the shame in the revelations, and, in the process, the memoir will structure itself and you will show up ”warts and all” – leaving a memorable impression that highlights your contribution to relationships and community.

Reflection

Being vulnerable is difficult as self-protection is our natural fall-back position. As we grow in mindfulness through writing, reflection and meditation, we can begin to draw back the veil that hides our imperfections and inadequacies. With the inherent growth in self-awareness and self-intimacy, we can become more real and more invested in telling the truth about ourselves. This is a progressive inner journey – a slow unveiling of our true inner self. By letting go of shame and expectations (our own and that of others), we can develop authentic connections, friendships and intimate relationships.

I wrote the following poem as a reflection on the negative impact of defensiveness on relationships and the power of vulnerability to create intimacy by removing our constructed barriers.

Sustaining a Relationship

Deceit destroys a relationship.

Closeness is beyond us, as we retreat behind the wall.

Facing up to who we are can be painful.

Without vulnerability, our relationships are shallow.

We hide behind our self-projected mask.

We engage our defence mechanisms.

We fence off our inner landscape.

Sustainability lies in vulnerability.

Openness to ourselves and others.

No longer the frightened child.

Now exposed to risk and reward.

Intimacy is in our hands, if we reveal who we truly are.

___________________________________________

Image by John Hain from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site and the resources to support the blog.