In a previous blog post I focused on agency and mental health – highlighting the mental health benefits that accrue when an employee is given the capacity to influence their workplace environment and to have a degree of power over the way things are done. How then does a manager create a workplace environment that is conducive to mental health through employee agency? One way to address this issue is for the manager to adopt an action learning approach.

Action learning and agency

Agency is a defining characteristic of action learning which involves learning with and through action and reflection on the consequences of your action, both intended and unintended. It is typically conducted in groups within a workplace where employees are collaborating to improve the work environment and the way the work is being done.

Reg Revans, the acknowledged father of action learning, argues that the best way to improve a workplace and the way the work is done, is to involve the people who have the “here and now” responsibility for the work. He suggests that you do not get a Professor of Medicine to solve the problems of nurses having to look after dying children – you get the nurses themselves together to explore the issues they are confronting, identify what creative solutions they could adopt and take action to implement them.

In the same way, Dr. Diana Austin found that the way to address the seemingly intractable problem of midwives experiencing trauma after the death of a baby and/or mother before, during or after birth, was to have the midwives share their thoughts and their feelings after experiencing such a critical incident.

In her presentation at the Learning for Change and Innovation World Congress in Adelaide in 2016, Diana explained that her research involved working with an “action group” of affected parties who gathered information about traumatic events and reactions from each other, from interviews with other affected parties and from external health professionals.

The “action group” identified the unconscious rules of the health professionals as the major impediment to improving the midwives’ work situation. The research resulted in the creative solution of an illustrated Critical Incidents e-book that addressed and challenged the fundamental assumptions underlying the unconscious rules. The e-book is now accessible to all health professionals throughout NZ and the world.

Diana explained that the research by the “action group” led to some key organisational outcomes:

- the conspiracy of silence about the personal impact of trauma after a critical incident was unearthed, challenged and removed

- destructive assumptions and unconscious rules were surfaced and challenged

- the e-book support package was created and made accessible to all

- new supportive processes were implemented and self-compassion was encouraged (refer: Austin et al, After the Event: Debrief to Make a Difference)

- a collaborative ethos was established that replaced the old ethos of “going-it-alone’ when suffering trauma after a critical incident.

Clearly, the activities of Diana and the “action group” not only improved the work environment and the way the work was done but went a long way to redressing the potential, long-term effects of experiencing trauma, by providing a supportive environment conducive to positive mental health. In the final analysis, the action learning by the group provided increased agency through the ability to change their work environment and the way trauma of health professionals was handled.

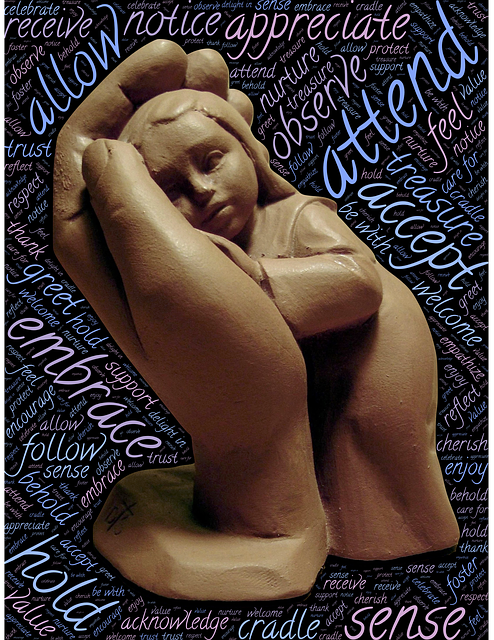

As managers and leaders grow in mindfulness, they are better able to facilitate action learning processes within their organisation, thus increasing the agency of employees and improving mental health.

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Image source: courtesy of Wetmount on Pixabay

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.