One of the aspects of self-awareness that is important to master is the assumptions we carry with us that impact our thoughts, perceptions, interpretations, emotions and behaviour. We can be aware of the negative impact on us of the assumptions of other people but be blind to our own assumptions and their negative impact on others.

Earlier I wrote about the impact for me of my social tennis partners making assumptions about my capacity to play tennis, given my age. Last week I fell into the same trap through my assumptions about another player.

I was playing social tennis with three other players, one of whom was a woman. She offered to play with the weaker player and I found this hard to accept initially because I assumed that she would be a weaker player, despite her size. This proved to be a false assumption as the woman player turned out to be the best player of the four of us.

The woman player had a particular style of hitting her ground strokes which meant that the ball levelled out when it hit the ground, making it very difficult to get a racquet under the ball. I spent most of the social game reframing my assumptions about the woman player and trying to counter her game.

The moral of the story is that assumptions can blind us to possibilities and reduce our capacity to cope with reality. Assumptions are like tunnels – they can distort our perception of others and of everyday occurrences.

Incorrect assumptions are often the cause of conflict in relationships because we tend to make assumptions about the motivation of the other person. They, in turn, make assumptions about our motivation and act on their own erroneous assumptions. We respond having confirmed in our own mind that our assumption about them were correct (confirmatory bias). And so a conflict spiral is created built on increasingly entrenched, but inaccurate assumptions.

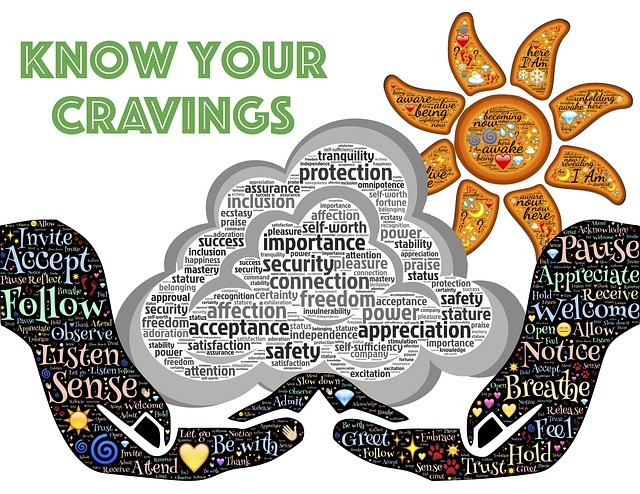

As we grow in mindfulness we become aware of the assumptions we hold, how they play out in our thoughts and emotions and how they are manifest in our behaviour. Through mindfulness we can increase our self-awareness in this area, better deal with the challenges of our life, enrich our relationships and develop our creativity.

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Image source: courtesy of Wokandapix on Pixabay

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.