Andrés Tapia, international inclusion expert, recently presented a webinar, Overcoming Hypocrisy: How Workplaces Move From Performative Allyship to Authentic Commitments, in which he explored how to mindfully develop inclusive leadership despite opposition within organisations. He highlighted the personal and career costs of attacking this laudatory goal in a mindless, unconscious manner. Andrés webinar was hosted by Berrett-Koehler Publishers, who published his co-authored book, Autentico: The Definitive Guide to Latino Success – which looks at bias, conscious and unconscious, as barriers to overcome if Latinos and Latinas are to get ahead. He also attacked the issue of inclusion from the leadership side when he wrote the book, The 5 Disciplines of Inclusive Leadership: Unleashing the Power of All of Us, co-authored with Alina Polonskaia.

In the webinar, he shared his experiences of developing inclusion in organisations on a worldwide basis. He noted that bias and exclusion are not the sole province of white, male-dominated organisations in the West. He indicated that exclusion exists everywhere but may manifest differently through bias on the grounds of religion, gender, ethnicity, skin colour or gender preferences thus having an impact on different groups, e.g., women, LGBT+, non-gendered, Muslims, Jewish.

Andrés explored several strategies for consciously developing inclusive leadership. His mindful approach included the following:

Be mindful of, and focus on, the people who are open to influence

Andrés warned against mindlessly attacking the problem of exclusion without awareness of the potential impact on mental and physical health and career success. He suggested that wasting time and energy on the extreme opponents to equity and fairness is exhausting, unsustainable and ineffective. He argues that you should seek out people in power who demonstrate an openness to inclusive practices and a willingness to explore the barriers, both personal and organisational, that perpetuate exclusion. This entails, in the initial stage, developing a conscious awareness of where other leaders stand on inclusion issues. It also means noting how inclusive are their friendships and social activities – what Andrés calls “foundational” evidence.

Develop allies

Exclusion is an arena of power so it is important to develop allies who will support and sustain you in your endeavours to create a counterculture that is compassionate and inclusive. Ignoring this advice can lead to burnout and isolation. Whenever, you are attempting to go against mainstream thinking and action, you need the support of others, both inside and outside your organisation. This is exactly what we did in establishing the Action Learning Action Research Association (ALARA) in 1991. At the time, action learning and action research were considered “aberrant” approaches to leadership development and organisational research – they were not mainstream and, in fact, challenged the very assumptions of the prevailing teaching, research and development culture.

Understand “bedrock principles”

In giving an illustration of a female executive’s support for the advancement of an Asian woman who had been discriminated against, Andrés maintained that the executive observed some “bedrock principles” for developing inclusivity – have a through understanding of diversity and inclusion concepts, develop awareness of an individual’s talents and capability, appreciate the importance of personal sponsorship and coaching, and draw on your courage to “step up” and “stand up” for what you know to be fair and equitable in the way individuals are treated. I have previously described the traits of inclusive leadership which reinforce Andrés concept of “bedrock principles”. He adds a further trait that he considers is frequently absent even among well-intentioned leaders – that is, an awareness of their own personal and positional power and a willingness to leverage this power in the pursuit of inclusiveness. Andrés points out that leaders often focus on empowerment of others who are disadvantaged but overlook their own power to create change.

Develop personal preparedness before seeking allies amongst disadvantaged groups

Seeking out allies amongst disadvantaged groups while being personally unprepared for the challenge of creating change puts an unnecessary burden on people in these groups who are already burdened by bias. Andrés suggests that you have to build your own preparedness for wise action through observation, reading , watching videos, listening to podcasts and engaging others in conversation. He suggests that this more mindful approach develops full awareness of the nature and extent of disadvantage experienced by a particular group of people, the origins of the underlying bias, and the complexity of the challenge involved in creating an inclusive culture. Mindfulness meditation can be employed to develop the necessary personal traits of inclusive leadership and awareness of our own unconscious bias. Andrés notes that we can draw inspiration from the example of companies like Discover Financial Services that deliberately located one of their call centres (employing 1,000 people) in one of the poorest, Black neighbourhoods of Chicago, in pursuit of economic diversity and economic justice.

Reflection

As we grow in mindfulness, we can increase our understanding of inclusion issues, develop self-awareness (especially in relation to our biases and their impact on others), build up the courage to intervene where necessary and gain the insight and creativity to take wise action. Developing inclusive leadership needs to be approached mindfully if we are to be effective in creating sustainable change in equity and fairness within our organisations.

_________________________________________

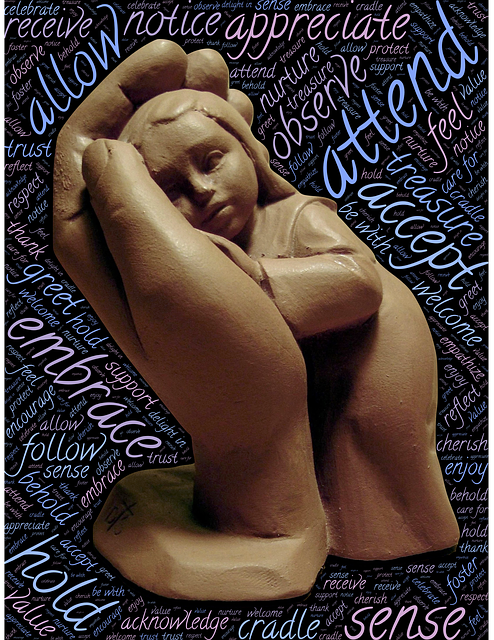

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group, and the resources to support the blog.