In a previous post, I explored Diana Winston’s discussion of the three dimensions of awareness – narrow, broad and choiceless. In this post, I want to explore “boundaryless awareness” which is often called “choiceless awareness“. I will be drawing on a guided meditation for resting in boundaryless awareness provided by Jon Kabat-Zinn.

The expansiveness of awareness

Jon reminds us that our awareness can take in an endless array of sensations, thoughts, and emotions as well as conscious awareness of the fact that we are observing, thinking or experiencing. Our awareness is like the unbounded expanse of the sky or the galaxies beyond.

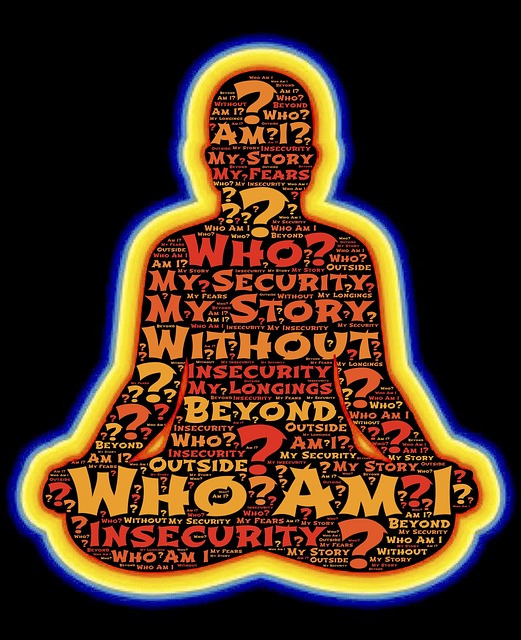

With narrow awareness we hone in on a particular focus such as our breathing, sounds around us or a specific self-story; with broad awareness we open ourselves to all that is going on around us. With boundaryless awareness we progressively open to our total inner and outer reality without constraint – not choosing, entertaining or engaging – just being-in-the-moment. Jon reminds us that we are often extremely narrow in our awareness, just fixated on ourselves – e.g. on our addiction, our pain or our boredom. Boundaryless awareness creates a sense of freedom – moving beyond self-obsession to openness to what is.

A guided meditation on boundaryless awareness

In Jon’s meditation podcast, provided by mindful.org, he takes us through a series of stages that gradually open our consciousness to the expansiveness of our awareness – beyond depth, breadth and width.

In the 30 minute meditation, he begins by having you focus on the “soundscape” – the sounds that surround you and the space in between each sound. He encourages you to “be the hearing” – to rest in the very act of hearing, thus deepening awareness not only of the sounds but also of the fact that you are hearing them.

In the next stage of progressing in awareness, Jon suggests that you now move your awareness to the air that you breathe and the sensation of the air on your skin as well as consciousness of its progress through your body. You could even extend this to breathing with the earth, so that you are attuned to your participation in the “breathing globe”.

Jon points out that while all this is going on your body is experiencing sensations – aches and pains, pressure of the chair on your back and legs, the sense of being grounded with your feet on the floor. [As I participated in this meditation, I even had the sensation of movement in my fingers (which were touching) – lightening the pressure of touch, growing thicker and expanding outwards.] Jon suggests that you let your awareness float across your body sensations as you breathe, sit, hear and feel.

You can extend your awareness to your thoughts, not entertaining them but growing conscious that you are thinking – letting your thoughts come and go as they float away. This awareness simultaneously embraces feelings elicited by your thoughts and accompanying images and memories.

In the final stage of this guided meditation, that Jon calls “one last jump”, you allow your mind and heart to be “boundless, hugely spacious, as big as the sky or space itself” – an awareness that has no bounds like the “boundarylessness” of awareness itself in its uninhibited form.

Stability through narrowing your focus

If you find that you need to stabilise your mind as you experience the unaccustomed sensations of “weightlessness” or unbounded awareness, you can return to a narrower focus – your breath or the sounds around you. In returning to a narrow awareness, you can sense the limits of this focus within the broader field of unbounded awareness. Boundaryless awareness, however, is accessible to you at any time you choose to pursue it.

As we grow in mindfulness by resting in our awareness -narrow, broad or boundaryless – through meditation, we come to realise the expansiveness of awareness and the freedom and calm that lies beyond self-absorption, with all its various manifestations such as addiction, negative self-stories or depression.

____________________________________________

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.