Social support can take the form of having friends, family or other people who can be a source of support in difficult times, such as chronic illness, death of a loved one or ongoing disability. They can provide emotional, companionship or resource support and enhance our self-image while offering different perspectives on what we are encountering.

Social support can be provided through a formal social network where people with common interests come together to achieve specific outcomes such as fitness, charitable work or a hobby (as with the Australian Men’s Shed). Alternatively, they can be informal where a number of people come together on a regular basis to share a coffee and have a chat.

The benefits of social support

Julia Baird, author of Bright Shining: How Grace Changes Everything, highlights the mental health benefits of social support and points to the research that shows the “poor mental health” that results from isolation and loneliness. She refers to a homeless support group organised by St. Vincent de Paul Society that she joined and noted that there was “no pretence”, people “just being who they are”. The healing power of this transparency and normality was evident in the homeless participants developing a positive self-image and contributing from their perspective and reality.

Social support is one of the three components for sustainable recovery from trauma, along with appreciating the complex nature of trauma and its impacts and adopting a holistic approach. Research and clinical practice have demonstrated that social support builds resilience in trauma sufferers – they realise they are not alone, are encouraged to pursue their healing process, are reinforced in their healing efforts and learn vicariously from others who are experiencing difficult emotions and challenging situations. The resultant sense of connectedness contributes to positive mental health.

The GROW organisation over many years has demonstrated that mutual social support has contributed to recovery from many forms of mental illness for hundreds of people (as documented in testimonial stories by participants). The peer-to-peer support process facilitated by a nominated leader within the “lived experience” group, promotes personal development and ongoing recovery – a process that may take a number of years.

Reflection

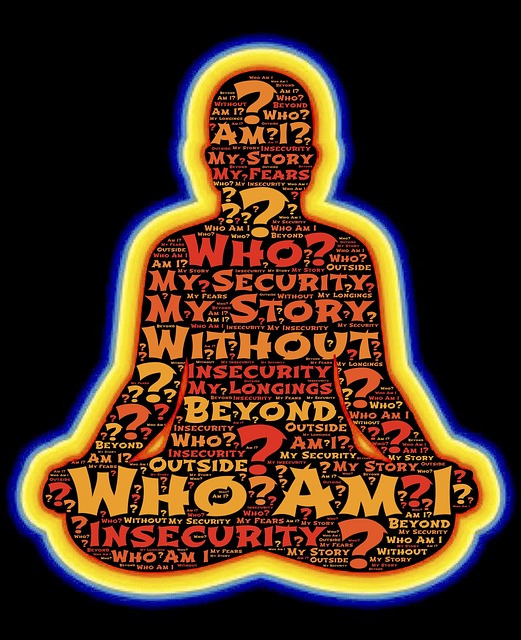

Social support helps participants to develop a sense of being cared for as well as feeling that they can seek assistance from others in understanding and managing their challenging situation. People gain a strong sense of belonging and connectedness through sharing their personal challenges, their success strategies and their progress towards healing. They grow in mindfulness as they share their stories and write about their insights, gaining increased self-awareness and heightened self-esteem.

Creative Meetups, provided by the Health Story Collaborative, is a powerful social support system in that it combines the healing power of social support with the healing power of storytelling. Participants feel fully supported by others engaged in compassionate listening or sharing their stories of challenging situations resulting from chronic illness, disability or their carer role. The following poem expresses the sense of social support that can be gained through the Creative Meetups:

Social Support

When we share our stories of personal challenges, we realise that we are not alone.

We draw strength from others experiencing and managing more difficult circumstances.

We sense that we belong and feel connected to something outside of ourselves and our pain.

We can be ourselves, free of pretence, unencumbered by the need to be “better than”.

We build trust, savour our relationships and look forward to the next encounter.

There is something magical and disarming about the process that leads to changing perspectives and healing.

____________________________________________

Image by John Hain from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site and the resources to support the blog.