Diana Winston offers a mindfulness meditation podcast, Working with Anxiety, as one of the weekly meditations conducted by the Mindful Awareness Research Center (MARC), UCLA. As Director of Mindfulness Education for MARC, Diana frequently leads these weekly meditations. She stresses that mindfulness enables us to be more fully in the present moment and to accept what is in our life (including anxiety) with curiosity and openness.

Diana maintains that mindfulness helps us to work effectively with anxiety because it, (1) enables us to be present in the moment, rather than absorbed in the past or the future; (2) facilitates reframing of our experience, and (3) provides a place of rest and ease from the turbulence and waves of daily life. As Diana asserts, anxiety is part and parcel of daily life, given the human condition and the uncertainty of the world around us today. The world situation with the global pandemic and devastating conflict between Russia and Ukraine add to anxiety-producing situations we experience on the home and local front. In consequence, there is an increase in mental health issues along with restricted resources to deal with explosive demand.

Guided meditation for working with anxiety

Diana’s approach is consistent with trauma-sensitive mindfulness in that she allows a choice of posture, meditation anchor and overall focus. She encourages us to find a posture that is comfortable with eyes closed or open (ideally, looking down). At the beginning of the meditation, she has us focus on something that gives us a sense of being grounded and supported by something of strength, e.g. our feet on the ground/floor or back against the chair. It is important to tap into something that enables us to slow our minds and calm our feelings

Diana then suggests that we focus on our breath as a neutral experience of the present moment. For some people, breath may not be a neutral aspect and could in fact trigger a trauma response. So, she offers an alternative focus such as sounds in the environment, the room tone or rhythm in some music. Whatever we choose as an anchor, we can return to it whenever we notice our thoughts distracting us and leading to anxiety-producing images, recollections or anticipations.

The next stage of the guided meditation involves focus on some source of anxiety and exploring the bodily sensations associated with it. Diana suggests that if we are new to meditation we should focus on a minor source of anxiety rather than a major issue. Whatever our focal anxiety source, the idea is to notice what is happening in our body, e.g. tightness around our neck and shoulders, quickening or unevenness of our breath or pain in our back. By bringing our consciousness to these bodily sensations, we can work to release the tension involved and restore some level of equanimity.

Diana suggests that at any stage we could use imagery as a way to achieve an anchor that gives us strength and/or a sense of peace. The image could be of a tall mountain withstanding the buffeting of strong winds and rain or a still lake reflecting surrounding trees and supporting the smooth gliding of swans or ducks. Imagery can take us out of our anxiety-producing imagination and transport us to a place of strength and/or peace.

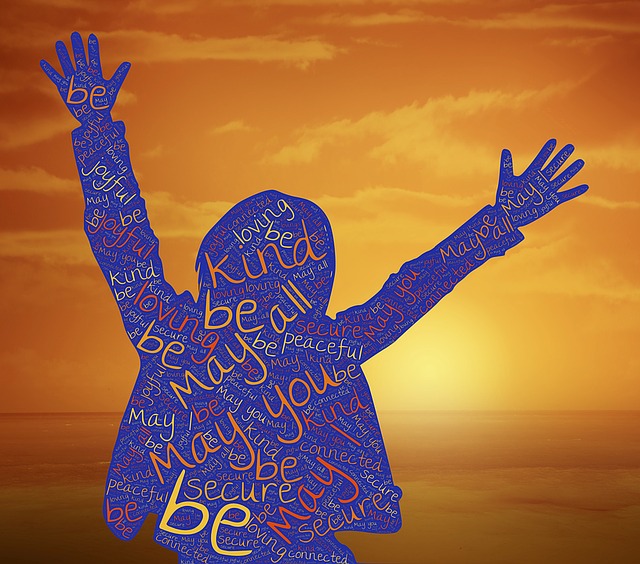

In the final stage of the meditation, Diana encourages us to offer ourselves loving-kindness, acknowledging that we are only human after all and that the world is anxiety-producing. She urges us to extend positive thoughts towards ourselves, rather then beat ourselves up for our fragility. We could focus on times when we have demonstrated resilience to overcome difficulties, extended compassionate action to those in need or expressed gratitude for all that we have.

Reflection

There are many tools to help us work with, and manage, anxiety. These include chanting and/or mantra meditations such as the calming mantra produced by Lulu & Mischka, Stillness in Motion – Sailing and Singing with whales. As we grow in mindfulness through meditation, chanting, mantras or other mindfulness practices, we can learn to be more fully present in the moment, to manage our anxiety-producing thoughts, regulate our emotions and find the peace and ease that lie within.

____________________________

Image by Patrik Houštecký from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group, and the resources to support the blog.