In a previous post, I explored the nature of harmful beliefs, how they arise and the negative impact they have in our lives. In this post, I want to focus on ways to challenge and manage these harmful beliefs and how to progressively break free of their hold over us – releasing the tight fist that constrains our interactions with others and blocks our creativity.

Again, I will be drawing on the wisdom and insight offered by Tara Brach in her new course, Releasing Negative Beliefs & Thought Patterns: Using Mindfulness to Break Out of the Trance. Tara argues that the way to break free of the hold of our false beliefs is to recognise them for what they are, investigate them and their impact in our lives and practice mindful awareness to ground ourselves in external reality, rather than live out a figment of our imagination.

False beliefs – their true nature

Tara explains that many of the beliefs we hold about ourselves and others are not only harmful but are untrue – they are false beliefs. She maintains that they are “true but not real”. The beliefs are true in the sense that we create them in our minds and experience them in our bodies – whether the tightness of fear, the restlessness of anxiety or the unsettled stomach flowing from worry. Tara cites Hildegard de Bingen who speaks of the impact of our beliefs in terms of creating an interpretation of reality – developing a mental map that is not the territory or as Hildegard describes the unreality of our self-beliefs, “An interpreted world is not a home”.

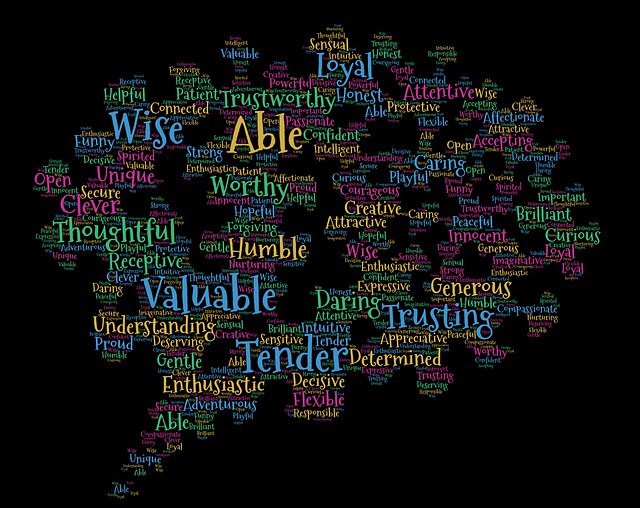

So, the starting point for loosening the hold of these false beliefs is to recognise them for what they are – an interpretation we impose on the world and people around us. We substitute our beliefs about ourselves and others for the real world – “we are unworthy and unlovable”; “they are more intelligent and resourceful”; “we do not deserve people’s appreciation or kindness”; “they are so much more accepted and accomplished than us”.

False beliefs can lead to “the disease to please”

False beliefs can lead to what Hariet Braiker describes as The Disease to Please. This “disease” manifests in a number of ways and can lead to “people-pleasing habits” designed to gain another person’s approval. The people-pleasing person puts the needs of everyone else before their own which leads to personal overload and ill-health. They may denigrate their own contribution and over-inflate the contribution of others. These behaviours are self-defeating because the perceived ingratiating behaviour is viewed by others as insincere and “over-the-top” – thus negatively impacting significant relationships.

False beliefs about oneself lie at the heart of these habits and are reflected in a mindset that “being nice” will ward off rejection or harm by others – a potential rejection or harming perceived as warranted by us because we believe that we are “unworthy” or “unlovable”. These deep-seated, self-beliefs can arise from past adverse or traumatic experiences, including abuse by our parents or others.

Investigating false beliefs

Tara suggests that false beliefs about ourselves and others can be sustained by us because they are never subject to investigation or personal inquiry. She provides a series of questions that can help with this inquiry and lead to enhanced self-awareness. I have reframed the questions below which can be explored in a meditation session on a conflictual encounter or a blocked endeavour:

- What is my belief that is getting in the way? – naming the belief to tame its impacts

- How true is this belief or is it simply untrue?

- What happens for me when I entertain this belief – in what ways do I suffer, and my relationships/endeavours suffer, because of this belief?

- What would my experience of relationships (or of the achievement of creative endeavours) be like if I no longer entertained this belief?

Tara suggests that the release from false beliefs is a progressive “letting go” that can be blocked sometimes by our need for control. In letting go of false beliefs, we can experience uncertainty and insecurity because we have created a vacuum – we have not replaced these beliefs with ones that are grounded in reality. Through meditation, we can learn to substitute beliefs that affirm our worth, our lovability and our good intentions.

As we grow in mindfulness through meditation on conflicted situations or blocked endeavours, we can name our false beliefs, challenge their distortion of reality and loosen their hold on us. This will free us to engage more fully and positively in relationships and release our energy for creative endeavours.

____________________________________________

Image source: courtesy of johnhain on Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.