Mark Mortensen and Heidi K. Gardner reported in a Harvard Business Review article that dozens of companies are reporting declining trust in the Hybrid Workplace model, both amongst employers and employees. They point out that in the early days when the Pandemic hit, people were forced to work from home because of isolation requirements. In that environment, when everything was in turmoil and everyone was “in the same boat”, there was a lot of tolerance and trust within organisations, despite the existence of some forms of hybrid workplaces. However, now with the reduction in the Covid19 presence and associated risk, and the return to workplaces (for some of the time), the level of tolerance and trust has dropped.

The authors attribute the decline in trust to a number of factors including the lack of preparedness of employees for home-based work (such as the absence of established routines), inadequate home technology, and the unpreparedness of organisations to facilitate information flow. While the majority of people at some stage had to work from home (because of lockdowns), this prevented employers from choosing the most appropriate employees to work from home. The problem now is that employees have the very strong expectation that working from home for some part of the week is part of their revised, return-to-work employment contract. They have experienced the real benefits of working from home in terms of flexibility and reduction in travel time and associated costs. Some employees experienced heightened productivity and the associated sense of accomplishment.

Now employers are faced with many more employees wanting to work from home with high expectations of this highly desirable condition being granted. This then raises equity issues for employers in terms of who to allow to work from home now, the number of days that people need to be at work and what days of the week individuals will be allowed to work in their home environment. It is interesting that in Brisbane City at present, Mondays and Fridays are very quiet traffic days (and there is plenty of parking at railways stations), while the other days of the week have returned to normal traffic flows and associated peak hours and delays.

Declining trust within hybrid workplaces

There is a problem that not everyone is suited to a work-from-home environment and not every home environment facilitates effective at-home work. Desirable traits for work-at-home employees include initiative, ability to work autonomously, reliability, results oriented and resilience. If employees lack the desired qualities to be effective working from home then a manager’s trust in their capacity and quality of output is eroded.

While people are working from home, there is a reduced opportunity for workplace relationships to develop through such random activities as the “water cooler chat” which has clear benefits for communication flow, collaboration and team-building. The resulting limitation on relationship-building impacts on levels of trust and tolerance amongst co-workers.

In the absence of “line-of-sight” for managers and supervisors there is a declining level of trust in how employees are spending their working day at home. Many managers and supervisors report that they don’t trust their employees working from home because they “can’t see what they are doing”. Mark and Heidi report that this has led to increased remote surveillance via electronic monitoring (e.g., keystroke counts) and virtual visual monitoring such as webcams and drones. All of which communicates to the employees that their managers do not trust them – which, in turn, impacts the reciprocation of trust (from employee to employer).

How to rebuild trust in a hybrid workplace

There are many strategies for building trust within a team, especially in a hybrid workplace. Below are some suggestions:

- Create culture change: Lynn Haaland suggests that managers of hybrid work teams can actively promote a “speak up culture” so that issues are addressed in a timely manner. The willingness to share what is not working well is even more paramount within the hybrid context as dissatisfactions can fester and lead to conflict and lower productivity.

- Provide guidance for working from home: Many people have written about how to be productive while working remotely. Managers can share the best suggestions and facilitate team exchanges of what works well for individuals in their home environment.

- Demonstrate trustworthiness: Mark and Heidi stress the importance of understanding that trust is “reciprocal and bi-directional”. This puts the onus on the manager to demonstrate trustworthiness in their words and actions and to align them so that they are perceived as congruent.

- Be empathetic: Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman argue that empathy is one of the three key elements that build trust in a workplace team. They explain that empathy can be displayed by resolving conflict, building cooperation, providing helpful feedback, and balancing concern for task with real concern for employees’ welfare. Empathy also helps to build the manager’s own resilience in the face of the increasing demands of their hybrid workplace.

- Adopt regular “check-ins”: If the focus of these check-ins is staff welfare as well as progress on assigned tasks, this will demonstrate empathy and build trust. This focus involves being prepared to really listen to how an employee is feeling, whether they are coping and what they need to rectify what is not working well.

- Use collaborate planning processes: Collaborative planning processes such as Force Field Analysis (FFA) and Brainstorming facilitate on-going collaboration, the exchange of ideas and the development of a sense of connection. Genuine Involvement in planning processes develops employee’s sense of agency and demonstrates that their views are valued, trusted and respected.

- Establish cross-team projects: Going beyond the immediate team to develop cross-team projects with other teams that have a common interest, concern or problem, helps to build rapport and trust, to break down barriers and silos, and to generate new ideas and perspectives.

- Be a good role model: The Mind Tools Team suggest that being a good role model is central to rebuilding trust in the workplace. This involves honesty, transparency, avoiding micromanagement, clearly communicating expectations and being a team player (not putting own promotion ahead of the team’s welfare). It can also extend to modelling working from home.

- Undertake more conscious planning and thinking: Bill Schaninger in a podcast interview stressed the need for managers to put more planning and thought into how they manage their hybrid teams. The world and workplaces have changed dramatically with the advent of the Pandemic and the way we manage has to be re-thought and re-designed. We can no longer assume that it is “business as usual” but be willing to change and adapt and reinforce for employees that we are across their issues and the new demands on them.

Reflection

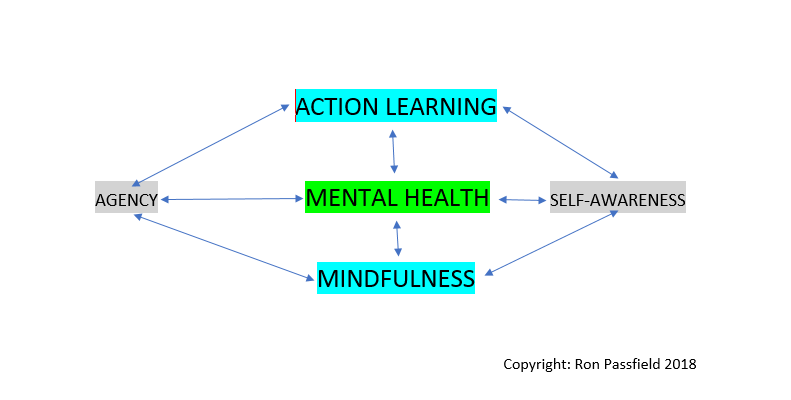

The demands on managers are increasing with the widespread adoption of hybrid workplaces. Yvonne Stedham and Theresa Skaar maintain that what defines a leader is their capacity to see a need for change, make things happen, and encourage others to engage in actions and behaviors that create a “new reality”. They argue that mindfulness is an essential trait/characteristic for leaders in these changing and challenging times. Yvonne and Theresa, on the basis of a comprehensive literature review, contend that as managers grow in mindfulness they are able to shift their perspective (re-perceiving), increase their flexibility and cognitive capacity, regulate their emotions and behaviour, and grow in self- and social awareness.

________________________________

Image by Ernesto Eslava from Pixabay

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group, and the resources to support the blog.