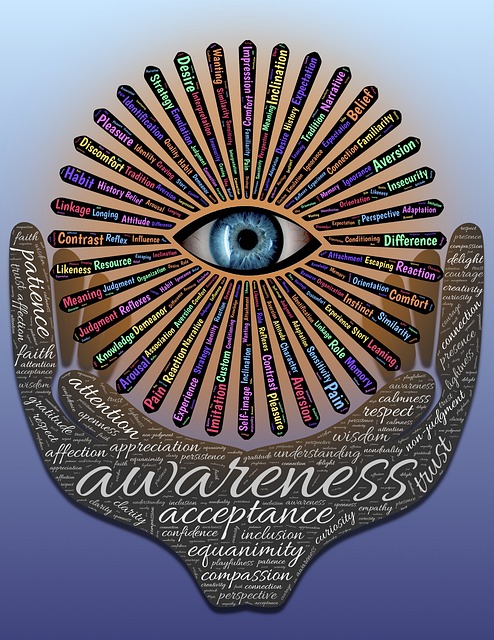

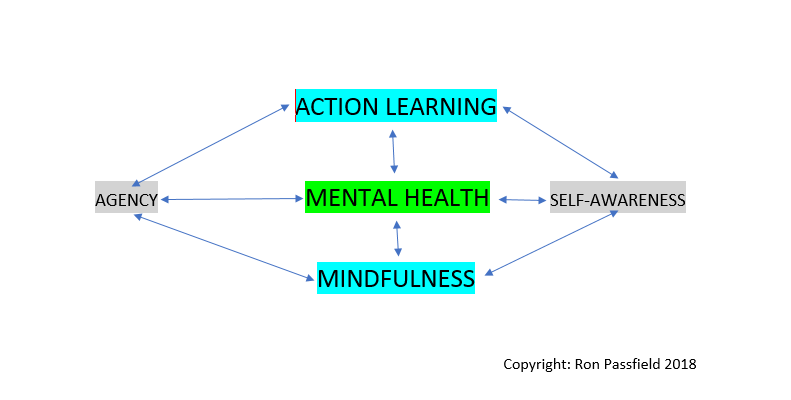

Over the past few months I have been exploring the linkages amongst action learning, mindfulness and mental health. I have found that action learning and mindfulness are complementary and enable the development of an organisational culture that is conducive to mental health. The image above represents my current conceptualisation of the relationships amongst action learning, mindfulness and mental health.

Mental illness in the workplace

The pressures of modern life have led to the increasing incidence of people in the workplace suffering from mental illness. This is compounded by the increase in the number of narcissistic managers. My own experience of consulting to organisations over many years has highlighted for me the urgency of taking action in the area of mental health in the workplace.

One particular consulting experience involved helping a manager and their group to become more effective. The senior manager exhibited high levels of narcissistic behaviours and the middle manager – while sincere and very conscientious – lacked self-awareness and interpersonal skills. This workplace environment was toxic for the mental health of all involved, including myself as a consultant.

Action learning and toxic work environments

In the course of my research and work as an organisational consultant and academic, I came across an action learning intervention in an educational context in South Africa that addressed the mental health issues resulting from a toxic workplace. This doctoral study has been published in article form and is described in my post on overcoming a toxic work environment through action learning.

Around the same time, I had the good fortune to study another doctorate that addressed the trauma experienced by midwives in a hospital in New Zealand. This research used action learning to change the culture from a punitive one to a culture that supported health professionals suffering trauma, reduced the impact of the traumatic event and enabled them to be more resilient in the face of the trauma experience. I discussed this case in my blog post on agency through action learning.

Creating a mentally healthy workplace through action learning

Reflecting on these two studies about action learning and toxic workplaces raised my awareness of the positive mental health implications of the action learning-based, manager development that I had been conducting with my colleague, Julie Cork, over more than a decade. I came to conceptualise that manager development program as creating a mentally healthy workplace through action learning. The perception of this program as developing a culture conducive to mental health in the workplace was reinforced by a report by two lawyers titled, Mental Health at Work.

When facilitating the Confident People Management (CPM) Program with Julie, we have the participating managers identify the characteristics of their worst and best managers. Then we ask them to identify their feelings when working for the best managers and then when working for the worst managers. Over more than a decade there has been almost unanimity over more than 80 programs in terms of the relevant managerial characteristics and the resultant feelings of subordinate staff. This is independent of whether the participants are from the capital city or regional areas and does not differ substantially amongst participants of different occupations and professions – whether the participants are police officers, doctors, lawyers, scientists, mental health professionals, nurses, hospital managers or public servants engaged in child safety, accounting or marketing roles. Participant managers know intuitively what managerial behaviours are conducive to mental health and what are injurious. We set about in the CPM to develop the characteristics of “good managers” in the program.

Mindfulness and mental health in the workplace

The research supporting the positive impact of mindfulness on mental health and its role in overcoming mental illness is growing exponentially. The ever-growing research base in this area led to The Mindfulness Initiative in the UK and the creation of the Mindfulness All-Party Parliamentary Group (MAPPG).

The benefits of mindfulness for mental health in the workplace were then documented in two very significant reports, Mindful Nation UK and Building the Business Case for Mindfulness in the Workplace. I have discussed this proactivity in the UK and the associated reports in a post, The Mindfulness Initiative: Mindfulness in the Workplace.

The Mindful Nation UK report incorporates feedback from the Trade Union Congress (TUC) which argues strongly that mindfulness alone will not solve the problems of toxic work environments. They contend that organisations need proactive interventions (not just isolated mindfulness training) to ensure that organisational culture is conducive to employee well-being. I have argued that action learning is an intervention that can develop a culture conducive to mental health.

In my discussions I take this conclusion one step further by contending that action learning and mindfulness are complementary and contribute to mental health through the development of agency and self-awareness.

Action learning and mindfulness as complementary interventions.

Reflection is integral to action learning and some mindfulness practices rely on reflection on events and personal responses to build awareness. I have discussed the similarities and differences in these reflective practices within the two approaches in a post titled, Mindfulness, Action Learning and Reflection.

Elsewhere, I have shown how action learning can contribute to the development of mindfulness through “supportive challenge”, mutual respect, equality and “non-judgmental feedback”. This discussion is available in a blog post, titled Developing Mindfulness Through Action Learning.

After discussing the complementarity between action learning and mindfulness, I wrote a reflection on the previously mentioned action learning intervention designed to change a toxic work environment in an educational setting. In this reflection, I discussed how mindfulness training could have helped the participants to exercise more fully the responsibility that came with agency. In a subsequent post, I looked at how mindfulness expands our response ability.

In a further reflection on both the doctoral studies mentioned above, I highlighted the capacity of mindfulness to break through the “conspiracy of silence” about mental health in organisations and to strengthen both self-awareness and resilience.

The complementarity betwen action learning and mindfulness in terms of developing a culture conducive to mental health comes into sharper focus when we consider the contribution of each to “agency” and “self-awareness” in the workplace.

Action learning and mindfulness develop agency in the workplace

Drawing on the work of Tali Sharot, author of The Influential Mind, I have shown how agency is a necessary prerequisite for mental health in the workplace. I have also explained how action learning can contribute to both employee agency and managerial agency. One of the things that stop managers from providing employees with agency (control over their work environment and the way their work is done) is fear of loss of control. Mindfulness enables a manager to overcome this fear, provide agency to employees and grow their own influence in the process.

I contend further that mindfulness enables agency to be sustained in the workplace for both managers and employees. Managers are better able to realise their potential by “letting go” and enabling employee agency. Employees, in turn, build their capacity to take up the agency provided through their own pursuit of mindfulness. “Sustainable agency” is an organisational condition that provides a nurturing environment for managerial and employee growth and for the mental health of all concerned.

Action learning and mindfulness develop self-awareness in the workplace

When you look at the underpinning philosophy of both action learning and mindfulness you find that both actively work towards achieving self-awareness by removing the blindness of false assumptions, unconscious bias, prejudice, and self-limiting “narratives”.

Action learning and mindfulness can thus act together to build self-awareness, a precondition for mental health. In the process, they provide the payoff from self-awareness in terms of increased responsiveness, creativity and self-management. Action learning and mindfulness also enhance self-awareness by encouraging us to admit what we do not know.

As managers grow in mindfulness through mindfulness practices they are better able to contribute to action learning and to build a culture that is conducive to mental health. Mindfulness helps both managers and employees to develop deeper self-awareness and to build their capacity to take up the agency provided, thus leading to a more sustainable organisational capacity for agency.

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Image source: Ron Passfield, Copyright. 2018

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.