I belong to an online group that meets once a month to share their stories of chronic illness and healing, both orally and in writing. These Creative Meetups are sponsored by the Health Story Collaborative (HSC) and are designed to enable participants to access the healing power of storytelling.

In our December Meetup, Jennifer Harris (our facilitator) introduced the theme of the winter solstice and the related concept of moving from darkness to light. The winter solstice is the time of the year when we experience the longest night and shortest day, signalling the transition from Winter to Spring. The event occurs at different times in the Northern Hemisphere (December) and the Southern Hemisphere (June).

Throughout history, the symbolism of the transition from darkness to light, represented by the winter solstice, has been celebrated around the world through rituals and festivals. There is also a very rich core of poetic expression around the theme of the winter solstice revealing the embedded sub-themes of rest, recuperation, replenishment and transformation.

Winter too is a time of transition for animal and plant life. Animals, for example, often withdraw from the bitter cold of winter and undergo some change in their habitat, feeding and outward appearance. They will prepare and change to meet the challenge of winter and, in some cases, hibernate so that they can survive.

The challenge of winter and wintering – moving from darkness to light

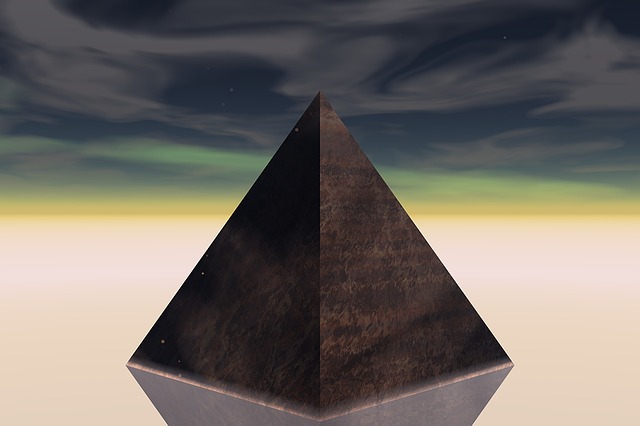

Katherine May, captures the essence of the challenge of transitioning from darkness to light in her book, Wintering: The power of rest and retreat in difficult times. She recounts her personal story of dealing with darkness in her life and her struggle to discover the light that would lead to her transformation. Katherine initially treated the advent of darkness in her life as a source of humiliation but came to realise that the darkness, like the transition from day to night, is “inevitable”.

Darkness for Katherine descended in the form of illness- undiagnosed autism and depression, as well as death in the family. She found the resultant involuntary period “lonely and painful”. Her tendency, like that of many others, was to withdraw, hide from public view and “show a brave face” whenever she could not avoid appearing in public.

Ivan Cleary, Head Coach of the Penrith NRL team, who suffered from depression during his football coaching career, found it a “humbling experience” and sought to hide the fact and withdraw from interaction with people. However, he found strong social support through his wife, Bec, and family members. After his second bout of depression, he learned to share his story with others and to model openness about his condition for the welfare of his players. Katherine, too, found that sharing her story, rather than hiding away, was healing. In telling her story to others, she found that there was a “shared thread in their story and mine”.

Learning to invite winter in

After a period of resistance, Katherine learned that “wintering” was a process of reflection and renewal and she gained a sense of “its length and breadth”. She began to understand that wintering was “not the death of a life cycle but its crucible”. She was able to recognise the wintering process and “engage with it mindfully and even cherish it”.

Katherine realised that inviting the winter in involved acceptance of her current health condition (and the nature of the human condition) while making adjustments to achieve ”a comfortable way to live till Spring”. She found that wintering could create insightful and profound moments in her life. Katherine concluded that “wisdom resides with those who have wintered”. Novelist Olga Tokarczuk reinforces this view in her book, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, when she has a key character conclude that “sometimes I think that only the sick are truly healthy”.

My own recent darkness

Over the past month, I have experienced a personal winter and attendant darkness. My daily life was upended by several concurrent events:

- A friend and colleague dying of cancer

- A close friend and co-author/co-facilitator (over 16 years) suffering a major stroke

- A serious illness of one of my adult sons

- A major flare-up of my MCAS-fuelled dermatitis.

As a result of these events, I have experienced grief, sadness, frustration, panic, and debilitation. The social support of my Creative Meetup group, where I have shared my story online, has helped me cope with these challenges. I am slowly emerging from the darkness as I acknowledge and accept my condition and begin to reach out to let the light in.

Letting the light in

During our Creative Meetup session focused on the winter solstice theme, Jennifer suggested that we write a letter to ourself, our body and/or the year ahead about what it means to let the light in. I found that I was able to identify some ways that the light was beginning to penetrate my darkness:

- Discovered the power of intentional breathing

- Became aware of a new hyper-sensitivity to soy products

- Discovered that an infection from a tick bite contributed to my flare-up (resulting in the MMA allergy – Mammalian Meat Allergy)

- Gained a referral to a specialist allergist to understand and manage my MCAS

- Received strong support, TLC and understanding from my wife

- Revisited the healing power of nature through Louie Schwartzberg’s visual meditations incorporated in 21 Days of Gratitude

- Drew on the inspiration of my son’s resilience

- Obtained medical assistance from a hospital Emergency Department.

Reflection

It appears that wintering is a natural part of the human condition. Our normal tendency is to deny our condition and to hide it from public view, whatever form our darkness takes at different stages of our life cycle. However, if we engage our winter mindfully and embrace its learning opportunities, we can experience renewal and growth, increasingly realizing our human potential. Katherine reminds us that there can be “a quick onset” of winter or a “slow drip”. Whatever way it occurs, we can use the inherent challenge of darkness to grow in mindfulness and emerge into the light, wiser and more resilient.

I created the following poem after reflecting on our discussion of the winter solstice and reading Katherine’s book on “Wintering”:

Letting the Light In

The darkness engulfs me:

a major stroke suffered by a close friend,

the death of a colleague,

serious illness of a relative,

MCAS flare up – dermatitis gone mad,

the light blocked out.

Wintering brings wisdom, resilience and regeneration:

without winter, there is no transformation,

without breath, there is no life,

without darkness, there is no transition to light,

without challenge, there is no growth,

without sickness, there is little wisdom.

Letting the light in:

accepting what is,

seeking out glimmers,

searching out options,

acknowledging the power within and without,

accessing agency to accelerate healing,

admiring the resilience of the healing journey of others,

savouring accomplishments achieved under difficulties,

connecting with others to gain strength.

Being gentle with myself:

sustaining my heart in the midst of heartlessness,

searching for hope in a poem,

seeking intimacy and connection,

finding sustenance in writing poetry,

expressing chronic pain and frustration,

sharing my story with others,

adjusting my expectations,

savouring freedom and life,

meditating on nature.

___________________________________________

By Ron Passfield – Copyright (Creative Commons license, Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives)

Disclosure: If you purchase a product through this site, I may earn a commission which will help to pay for the site, the associated Meetup group and the resources to support the blog.